The Story of James Henry Breasted (1865 -- 1935) told by his son Charles is a poignant story of one of the most brilliant scholars of all time. Charles, who died in 1980, first published the biography in 1943, and it is appropriate that it should be reprinted this year as we celebrate the 90th anniversary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, which Breasted founded with the support of D. Rockefeller Jr.

Breasted's vision was to create an interdisciplinary research centre that would unite archaeology, textual studies and art history as three separate yet complementary specialisations, thus providing a clearer understanding of ancient civilisations.

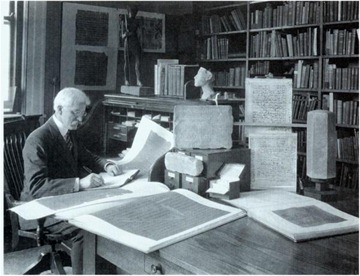

In this engaging account, which on many levels is more compelling than fiction, Charles Breasted (1897 -- 1980) takes us into the academic and personal life of his father, the holder of America's first Chair of Egyptology and one of the most prolific scholars of his day. His 5-volume Ancient Records of Egypt, which systematically recorded and translated all the inscriptions he could find in Egypt, remains unmatched. The accounts of some of his expeditions reveal a staggering determination in often harrowing circumstances, while his failures (and they were numerous) make painful reading. Breasted's sorrow was sometimes deep, but his successes were astounding. This is the story of one of the "greats" in Egyptology, and his son does not fail to include in this biography other "greats" of his era.

Two things are clearly apparent in this biography. One is that the author is a gifted writer who grasps the essence of what he wants to say, and describes it with eloquence; there is a rhythmic flow to his descriptions. The other is that he inherited this gift from his father. Breasted the son, a writer of not inconsiderable talent, in some places draws liberally from the field notes of his father, and I not infrequently found myself checking whether I was reading James Breasted's original text or his biographer's record. There is no doubt that Breasted the son's travels with his father inspired him, that he himself learned his father's profession from the close contact between them, and that writing his father's biography was a labour of love.

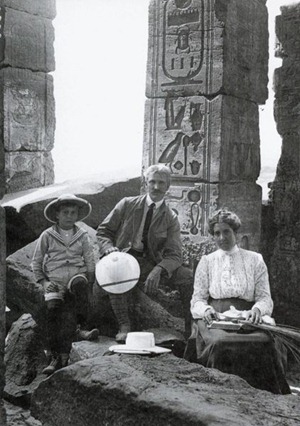

James Breasted's wife Frances, Charles's mother, plays an important part in the book, and this too provides considerable colour to the central theme of excavation, discovery and documentation. Frances was a Victorian damsel, demure in her long skirts and high-necked, long-sleeved blouses, yet an adventurer too. In her travels with her husband to Egypt, Mesopotamia, Syria and Palestine, she climbed volcanoes, rode rapids in canoes, mounted camels, braved desert discomforts and the lack of facilities, but was also, as her son reveals, a dependant and demanding woman who did not like being left alone. Yet her husband was away most of the time -- if not physically then certainly mentally when family interests took second place to intellectual pursuit and proclivity for adventure.

She had great sympathy for the needy. "Whenever we moored near a village, all the halt and the blind, the sick and the injured who could be carried or led, would gather on the river bank beside the boat and beg to be cured -- for the impression persisted among them that every white person was a doctor ... Ninety-five percent of the population suffered from some form of highly infectious ophthalmia, predominantly trachoma; while to the other diseases especially prevalent in the orient were added most of the ailments and injuries afflicting humanity in general. My mother was indefatigable in doing what she could for these sufferers, and in extreme cases my father would interrupt his work to draw upon his pharmaceutical knowledge for such remedies as our modest medical supplies would allow".

James entrusted his wife with the duties of expedition housekeeper. "She fulfilled these with a conscientious perfectionism which kept the little household in a state of chronic ferment and on several occasions provoked open mutiny among the Nubian servants and crew. She had the habit, whenever domestic crises occurred, of writing notes to my father, even though he might be in the very next room; and as far back as I could remember, I had been their involuntary bearer," recalls Charles.

In the early years of the 20th century the purchase of antiquities was not restricted. Antiquities for museums in Europe and America were routinely purchased from dealers and legally exported, albeit with the permission of the Egyptian government. Breasted himself purchased hundreds of objects that today enrich the collection of the Oriental Institute Museum. Some he acquired for their beauty and artistic value, but more frequently they were objects that could be best used as instructional aids.

In the early years of the 20th century the purchase of antiquities was not restricted. Antiquities for museums in Europe and America were routinely purchased from dealers and legally exported, albeit with the permission of the Egyptian government. Breasted himself purchased hundreds of objects that today enrich the collection of the Oriental Institute Museum. Some he acquired for their beauty and artistic value, but more frequently they were objects that could be best used as instructional aids.On his relationship with his son, let Charles speak for himself: "The bonds which these early years forged between us, and the seeds of the sympathetic understanding of his hopes and dreams which they implanted in me, were one day to bring us together in a working association such as is seldom permitted between father and son. Yet I was never able to conquer nor he to understand the overwhelming depressing effect upon me of the dead world which was his supreme inspiration. He found it incomprehensible that the vast material residue of the life of man on earth, neatly arranged in the tomb-like, musty silence of a thousand museum halls and galleries and basements, from which of late afternoons I had for years been taken to fetch him 'home', should gradually have filled me, even as a child, with an unbearable sense of death."

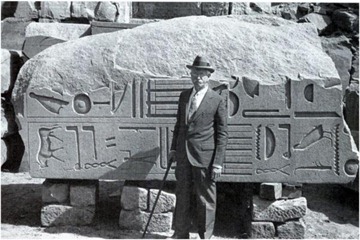

For James Breasted himself, it was all thrilling. "My words cannot convey the blood-tingling exhilaration of such splendid moments when the boat darts with a bird's swiftness down the tumbling, surging river," he writes in his daily diary on 27 November 1906 . On 21 January 1907 he finally locates the Nubian temple of Akhnaten known as Gem-Aten, this after days of "this inexorable north wind (that) has no mercy on us.... for the last nine days has raged without a moment's cessation....", and found that the wind still blew "so viciously as to make photography on a ladder almost impossible."

A discouraging day had brought him to the most important discovery in Nubia, and still he could not record it... because: "At noon today the wind quickened again into a furious gale which buried us in vast clouds of dust and sand like ashes from Vesuvius. There is a pungent odour of dust in the air, it grates between one's teeth, one's ears are full, one's eyebrows and eyelashes are laden like the dusty miller's, it sifts into all boxes and cupboards, penetrates between glass negatives, ruins chemical solutions in trays in the dark room.... Amenhotep III's great temple of Soleb is only thirty miles away. We could reach it on good camels in a day, but to face this storm on the open desert would put out one's eyes!"

Charles writes of time his illustrious father, standing on a ledge of granite cliffs above the camp in Nubia, slipped, lost his balance in the "terrific wind, and pitched headforemost more than twenty feet down onto some rocks below". By some miracle he was not killed. "I remember seeing him come reeling into camp, bleeding and stunned," Charles wrote. "We gave him brandy, disinfected and bandaged his ugly lacerations, [and] tried to persuade him to rest for the remainder of the day. But he quickly regained his composure and resumed work."

Charles writes of time his illustrious father, standing on a ledge of granite cliffs above the camp in Nubia, slipped, lost his balance in the "terrific wind, and pitched headforemost more than twenty feet down onto some rocks below". By some miracle he was not killed. "I remember seeing him come reeling into camp, bleeding and stunned," Charles wrote. "We gave him brandy, disinfected and bandaged his ugly lacerations, [and] tried to persuade him to rest for the remainder of the day. But he quickly regained his composure and resumed work."And on his father's work, Charles paints a compelling picture. "...week after week the work continued. Sometimes my father and his two assistants would be working high up on a rocky promontory overlooking a great stretch of the Nile, where three thousand years or so ago an official of an ancient Pharaoh had perhaps sat for many days, counting his sovereign's cargo ships as they brought tribute or imports from inner Africa -- ebony, ostrich feathers, ivory, captive animals, pygmies and the like. A combination of boredom and vanity often led such a man to carve on the rocks an inscription which in the neat hieroglyphs of a practiced scribe set forth his rank and station, his honors, the year of his Pharaoh's reign, and the date when he sat counting the royal ships".

Descriptions like these, alongside photographs of his family; work at various sites; camel expeditions in distant places; archaeologists at a formal luncheon set up in a tomb; Breasted laying the cornerstone for the new headquarters of the Oriental Institute in Chicago in 1930 and a formal portrait of him with his wife Frances in 1933, provide a splendid background to the story of one man's scientific dreams and eventual fulfilment. This was a man who wrote in 1912: "From the beginning of my career I looked forward to the systematic collection of the surviving historical material of the entire near orient, which I linguistically command. I am the first to appreciate the enormity of the task."

Years of scientific drudgery, of incessant travel, of "spirit-racking, white-collar penury," and continually frustrated hopes were endured before the name of James Breasted became synonymous with early archaeological exploration and research in the ancient Near East. Breasted gave himself over to an adventure that lasted his entire life, and he left a worthy record of achievements.

In the spring of 1912 he was able to write, and to deliver at the Union Theological Seminary in New York's Morse Lectures, a paper on his recently-published Development of Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt, regarded by critics as the ablest, most penetratingly thoughtful work he had yet produced. Remember, James Breasted had, in those early days, to pit himself against "the rather self- superior complacency of Old World scholarship like Britain's Flinders Petrie, France's Auguste Mariette, and Germany's Adolf Erman, whose careers were interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, political uncertainties, and other related problems.

In the spring of 1912 he was able to write, and to deliver at the Union Theological Seminary in New York's Morse Lectures, a paper on his recently-published Development of Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt, regarded by critics as the ablest, most penetratingly thoughtful work he had yet produced. Remember, James Breasted had, in those early days, to pit himself against "the rather self- superior complacency of Old World scholarship like Britain's Flinders Petrie, France's Auguste Mariette, and Germany's Adolf Erman, whose careers were interrupted by the outbreak of World War I, political uncertainties, and other related problems.This is the story of an American prairie boy who at 21 was a graduate pharmacist clerking in a drug store in Omaha; who was suddenly seized with the conviction that he "must preach the gospel"; who abandoned the ministry in favour of oriental studies, and as a result of his family's unlimited sacrifices and his own invincibility, won his doctorate in Egyptology at Berlin University, and was appointed to the first chair of Egyptology ever established in America, at the then embryonic University of Chicago.

Thanks must go to the publishers, The University of Chicago Press, for reprinting this original Charles Scribner 1943 publication - the biography of a pioneer written by his son in loving attention to detail. The thoughts attributed to various characters are, writes Charles in his Preface, based either on original correspondence and journals, or on descriptions given to him at various times by his father, by members of his family, and by old family friends. "I have followed those versions which seemed to be indicated by all the available evidence, or under the circumstances to be the most probable," wrote Charles in the Preface. "My reasoning and conclusions cannot always have been correct; and for any resulting inaccuracies I must assume full responsibility".

Possible inaccuracies notwithstanding, this is a book worth possessing and worth reading.

Author: Jill Kamil | Source: Al-Ahram Weekly [January 06, 2011]

http://archaeologynewsnetwork.blogspot.com.es/2011/01/digging-up-past-story-of-archaeologist.html

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario