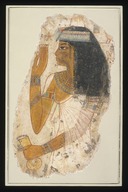

Crushed skull of a soldier with a

copper helmet

From Ur, southern Iraq

about 2600-2400 BC

about 2600-2400 BC

A guardian of the 'King's Grave'

This skull comes from the 'King's Grave' in the Royal Cemetery at Ur. The main tomb was in a rough stone chamber at the bottom of a large pit. The bodies of six soldiers wearing copper helmets and carrying spears lay at the foot of the ramp which descended to it, over eight metres below the modern surface. The helmets were broken and crushed flat by the weight of the soil which had been thrown back into the grave during the burial.The soldiers were presumably intended to be the guardians of the tomb for eternity. If so, they failed in their duty because the central tomb had been robbed in antiquity. Including the six soldiers, sixty-three victims in total, most richly adorned, filled the floor of the pit.

The soldiers' helmets closely resemble those worn by the soldiers on the Standard of Ur.

C.L. Woolley and P.R.S. Moorey, Ur of the Chaldees, revised edition (Ithaca, New York, Cornell University Press, 1982)

C.L. Woolley and others, Ur Excavations, vol. II: The R (London, The British Museum Press, 1934)

British Museum

britishmuseum.org